“PAYING A PRICE FOR OVERALL GOOD”

– Asheville Citizen title for Mall announcement 1980.

For nearly two years, the Save Downtown Asheville organization fought the development of the Strouse-Greenburg mall. The organization was made up of local business owners and concerned citizens. Following the announcement of the mall on March 13th 1980, people like Wayne Caldwell and Kathryn Long worked to gain support against the mall and argue against the destruction of North Lexington Avenue.

Immediately following the announcement of the mall, people began to meet at 25 Broadway to discuss how they were going to be able to keep their business. Kathryn Long, an Asheville native, owned Ambiance Interiors and her family owned the neighboring Sluder’s Furniture. Long’s brother-in-law, Wayne Caldwell, a fellow Asheville native, moved back to Asheville and worked in Sluder’s Furniture, after working as an English professor. He remembers reading about the mall in the Asheville Citizen, calling up Asheville Revitalization Chairman James Daniels immediately, and being shown the blueprints. Daniels then showed him just how serious the city was. Meanwhile Long heard about heard about the mall from Richard Thorton, a long-time friend of the Longs and employee of the city planning department. Thorton and many other people that worked for the city did not want to see the development of the mall. He advised Kathryn to come to the planning office, where she met Verl Emrick, the planning director for the city. Quickly the Longs, Caldwell, and the North Lexington community realized what they faced. That same week Caldwell started the Save Downtown Asheville organization and hired local lawyer Bob Long to help fight the city.[ref]Caldwell and Long, Interview with site author, March 12, 2015[/ref]

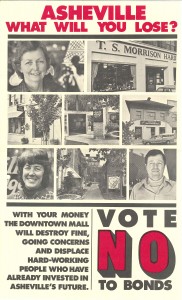

While the city officials had made the argument for the mall under the name Building a Better Asheville, local business owners had to fight for their right to remain in downtown. While the city officials sought to rush the development of downtown in a few years by building a mall, many business owners felt that the city was coming alive and that given more time, Asheville would prosper again. The city officials didn’t believe Asheville had enough time. Although many buildings were blighted downtown, local owners who had stayed reported that their businesses were thriving and did not want to relocate away from downtown. Thus the battle quickly became a legal obstacle course for Caldwell, Long, and Save Downtown Asheville.

At the first major public hearing, Save Downtown Asheville made it a goal to make sure that people knew just how much of the city was going to be  effected. The planning director of mall Verl Emrick faced a crowd greatly opposed to the development of a mall. Emrick first attempted to avoid discussing the speed of the development. Kathryn Long though presented the audience with the development timeline, signed by the city, illustrating the

effected. The planning director of mall Verl Emrick faced a crowd greatly opposed to the development of a mall. Emrick first attempted to avoid discussing the speed of the development. Kathryn Long though presented the audience with the development timeline, signed by the city, illustrating the

urgency for a community response against the mall. Long remembers “I said ‘I am taking this document to our attorney of Save Downtown Asheville’ and I rolled it up and I walked out.” And everyone watching television that night knew city development was serious. Quickly the city officials began to lose the battle of public opinion.[ref]Caldwell and Long, Interview with site author[/ref]

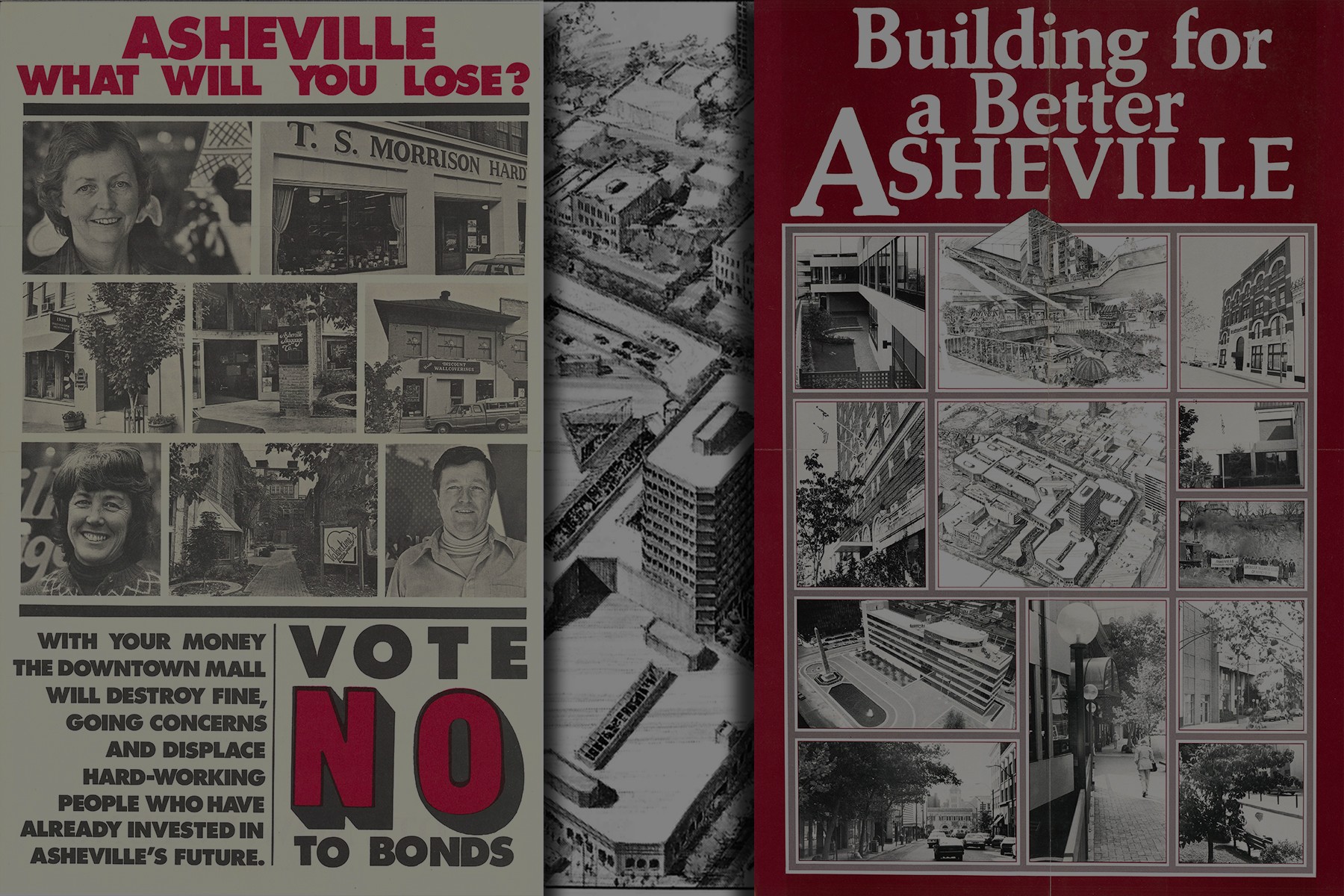

While the city tried to make the argument that the downtown of Asheville needed to be rejuvenated as a fast as possible, Save Downtown Asheville knew the city was coming back. They felt that Asheville could become strong again in ten, maybe twenty years. City officials believed that businesses simply did not have that much time to wait and see how the economy was going to recover. Thus many of the early advertisements for Save Downtown Asheville featured the faces of downtown and the people that owned the businesses or lived on the streets proposed to be demolished.[ref]Caldwell and Long, Interview with site author[/ref]

Money played a large role in the decision for building a mall. The city could only get money two ways, either from Revenue Bonds or from General Obligation Bonds. Revenue Bonds don’t require popular vote, while General Obligation Bonds do require popular vote. Upon hearing that the city was going to use General Obligation Bonds in August 1981, Caldwell went to Bob Long’s office. Following a big smile from Bob Long, he informed Caldwell that the battle had just become political. They would need to raise awareness by the voting day in November. They had only three months.[ref]Caldwell, “Rattlesnakes,” in 27 Views of Asheville: A Southern Mountain Town in Prose & Poetry, comp. Rob Neufeld (Hillsborough, NC: Eno Publishers, 2012), 131.[/ref]

In this video you can see Kathryn Long speaking on North Carolina Public TV in 1980 about the efforts to preserve downtown.