“The Asheville Downtown Commercial Complex (ADCC) was once an active, integral part of the central business district supplying goods and services to the citizens of Asheville, Buncombe County and Western North Carolina. Years of neglect, deterioration, and functional obsolescence of the buildings in the area have caused the area to become blighted and have a blighting influence of the central business district… This plan is an effort to accomplish a turn-around in the status of the area.”

– Asheville Downtown Commercial Complex Redevelopment Plan September 8, 1974 [ref]Housing Authority of the City of Asheville, and City of Asheville, Division of Planning. Asheville Commercial Complex Redevelopment Plan. PDF. Asheville: City of Asheville, August 1981, i.[/ref]

Asheville was not the first city in America to envision a mall as a economic savior; nor were they the first to consider ripping out their downtown area to make room for said mall. Downton, Inc.: How America Rebuilds Cities, Bernard J. Frieden and Lynne B. Sagalyn notes that in the 1950’s and 1960’s, while city officials across the nation struggled with their own revitalization projects, real estate developers hoisted malls throughout suburbia at a rate ten times that of previous years. By 1974 15,000 shopping centers were controlling 44% of the nations common retail sales, with 800 large regional malls making up almost a third of that total. The success of the suburban made the idea of using this model to revive American downtown areas very temping among communities.[ref]Bernard J. Frieden and Lynne B. Sagalyn, Downtown, Inc.: How America Rebuilds Cities (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1989), 69.[/ref]

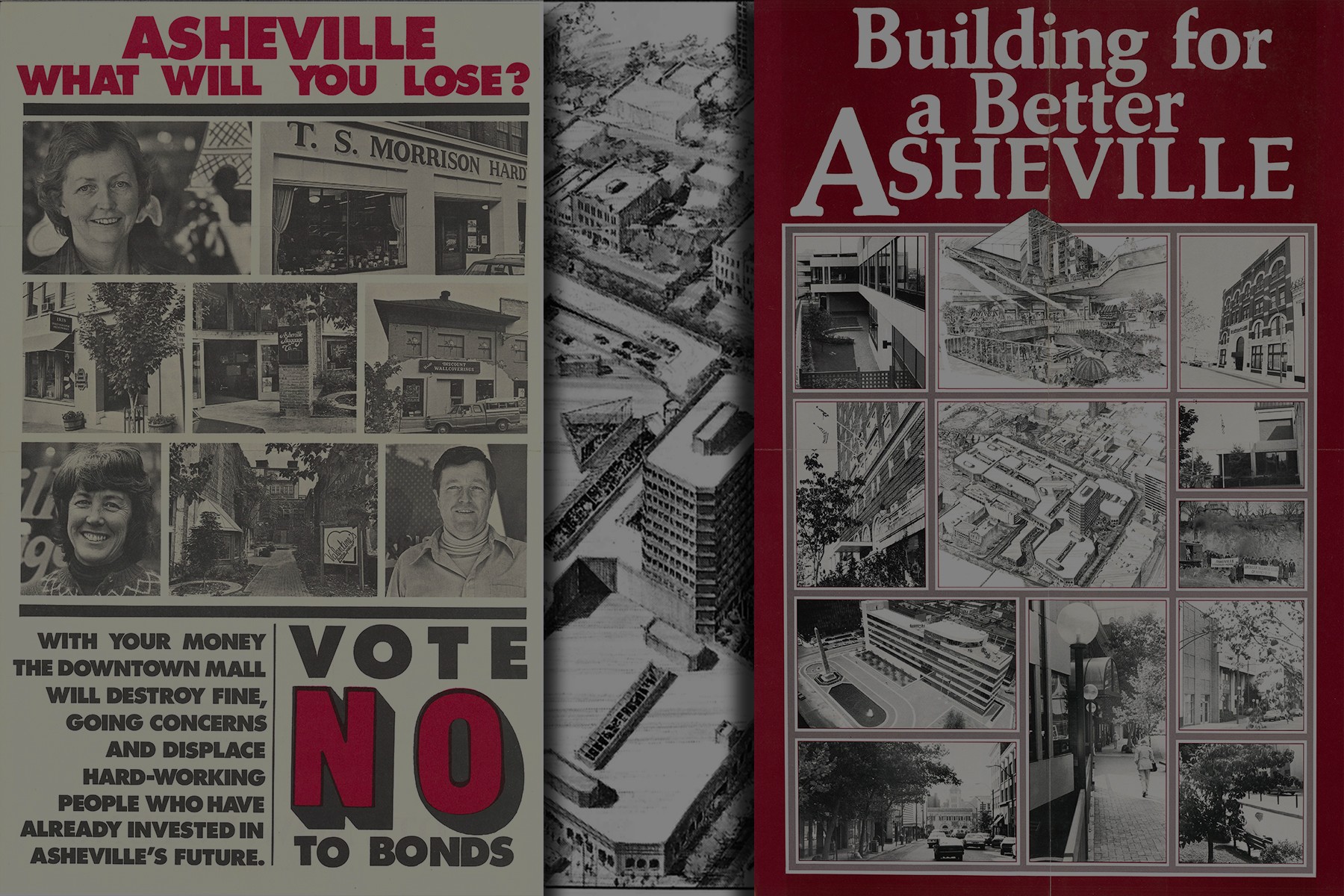

At this time, Asheville was no stranger to shopping centers. Nan Chase’s Asheville: A History notes that a mall had already came to the Tunnel Road suburbs by 1974, but it did more to hurt economic function than it did to help. As the baby-boomers filled the countryside, suburban development followed. The growing reliance on automobiles that began in the 1950’s lead to a drop in the use of public transportation that was centered in downtown. When people stopped going downtown, businesses had to follow, either by moving to the new mall in the suburbs or closing up shop. In any any case, Downtown Asheville emptied. The Tunnel Road mall crippled Downtown and rendered an economic wasteland for the next 20 years.[ref]Nan K. Chase, Asheville: A History (Jefferson, NC: McFarland &, 2007), 165-170.[/ref] In spite of the Tunnel Road mall’s deteriorating effect, Downtown had already been suffering from blight and politicians followed suit with other cities in the nation who felt they needed, as Friedman and Sagalyn words it, a “brick-and-morter” symbol to prove they could turn the city around and erase the blight consuming Downtown.[ref]Bernard J. Frieden and Lynne B. Sagalyn, Downtown, Inc.: How America Rebuilds Cities, 281.[/ref]

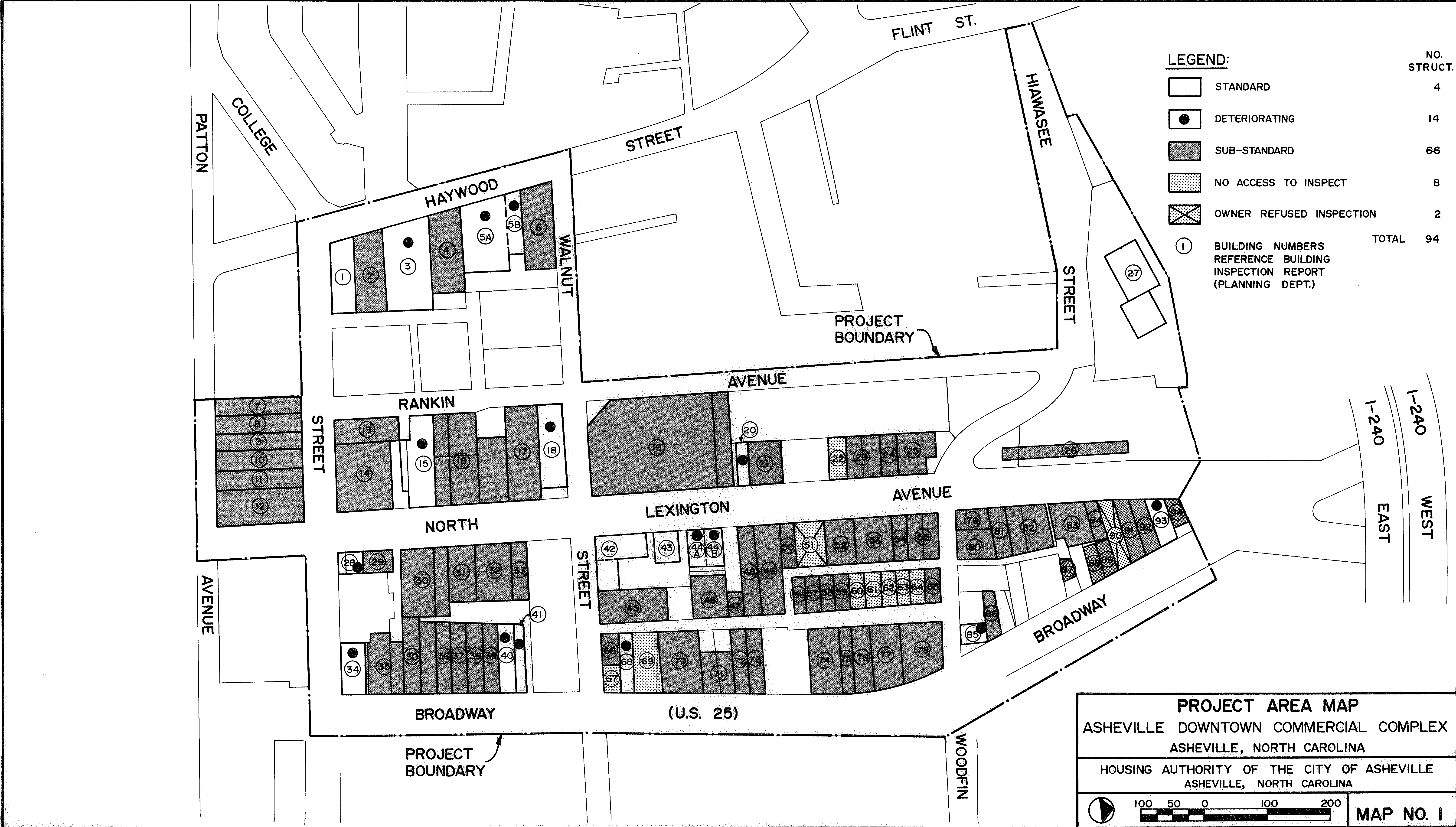

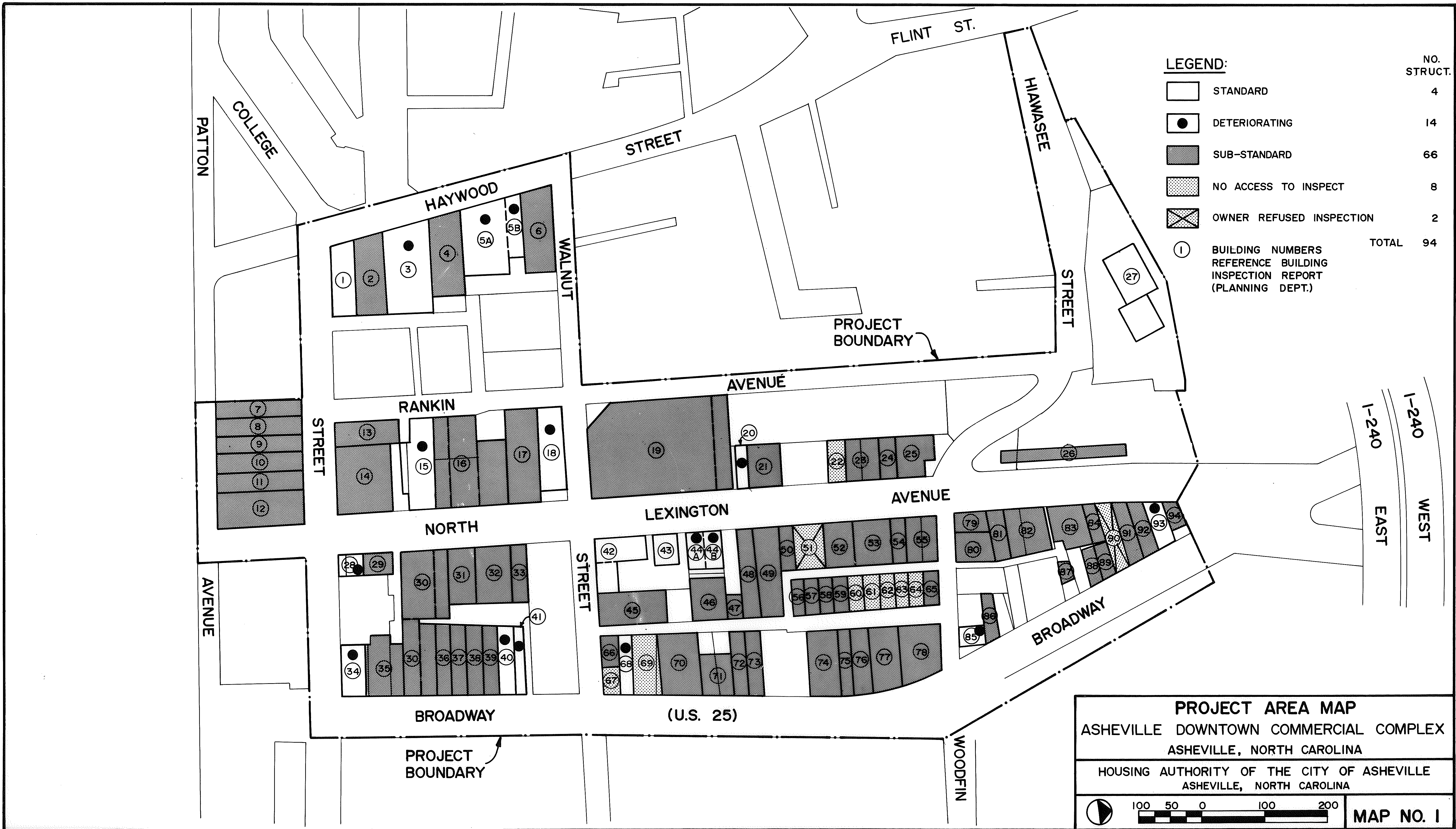

Sager’s history of the would-be mall notes that former Asheville mayor Gene Ochsenreiter and local business leaders would form a committee to assess the state of Downtown. What became known as the Asheville Revitalization Commission (ARC) announced the plan study the project. Plans were soon announced for the redevelopment of the pitiful urban center by establishing a new downtown commercial complex. Major support for the project from city officials and civic leaders. ARC teamed up with many Downtown business owners to put backing behind the revitalization project. This new mall would serve as a joint revitalization between the City of Asheville and a private developer, Strouse, Greenberg & Company out of Philadelphia. Sager also notes that City building inspectors began surveying the buildings in the Lexington Park area in May of 1980. The inspectors were looking at the structures to see if they met current (1980) building codes. None of the 85 buildings were up to code. Even the most modern of Downtown Asheville’s buildings did not meet current codes of 1980.5[ref]Sager, Molly. “The Mall That Almost Ate Asheville: The Fight between City Hall and Save Downtown Asheville Inc. Over the the Strouse, Greenberg & Company Downtown Commercial Complex.” (Undergraduate thesis, University of North Carolina Asheville, 2012.), 10.[/ref]

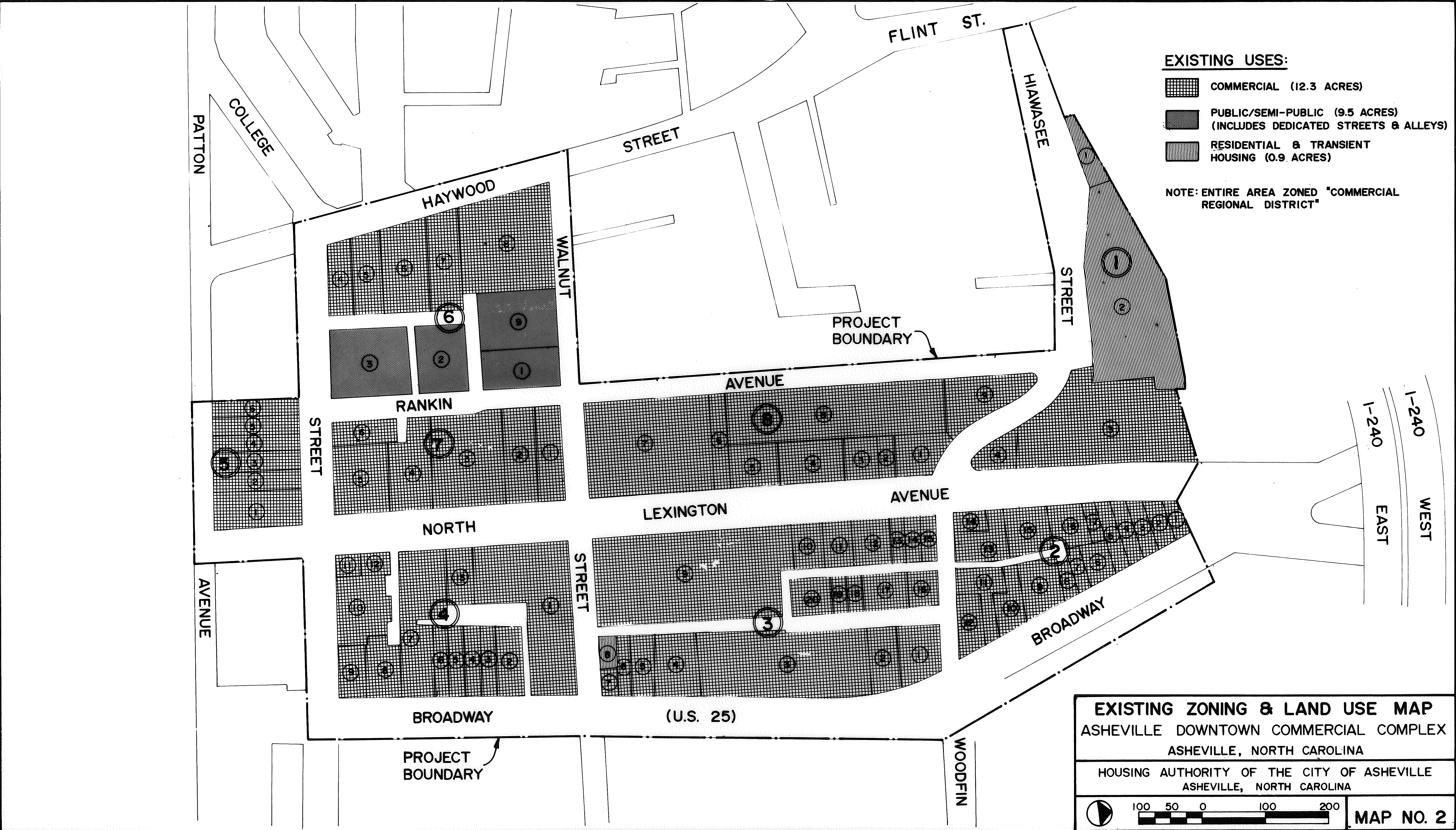

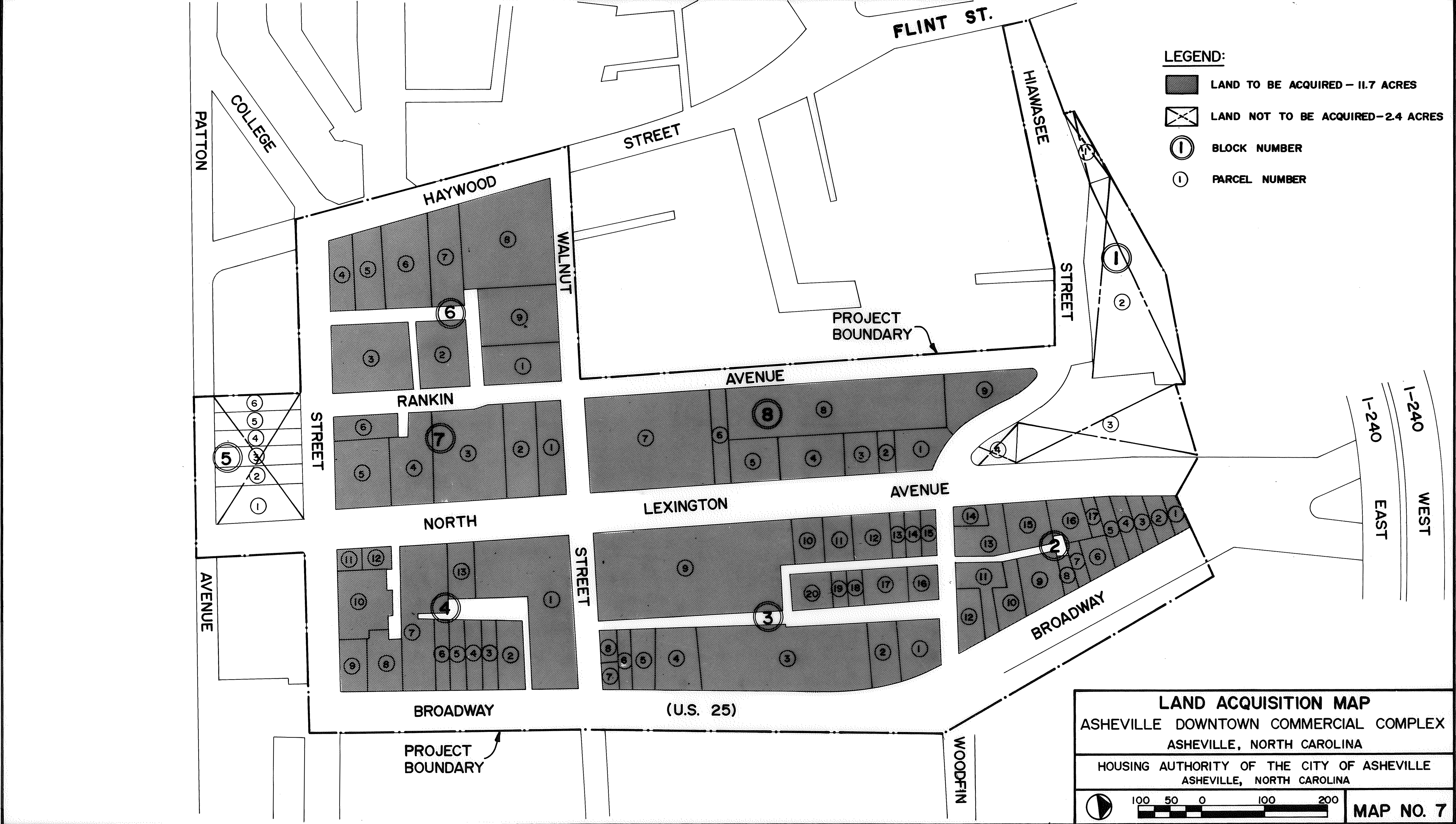

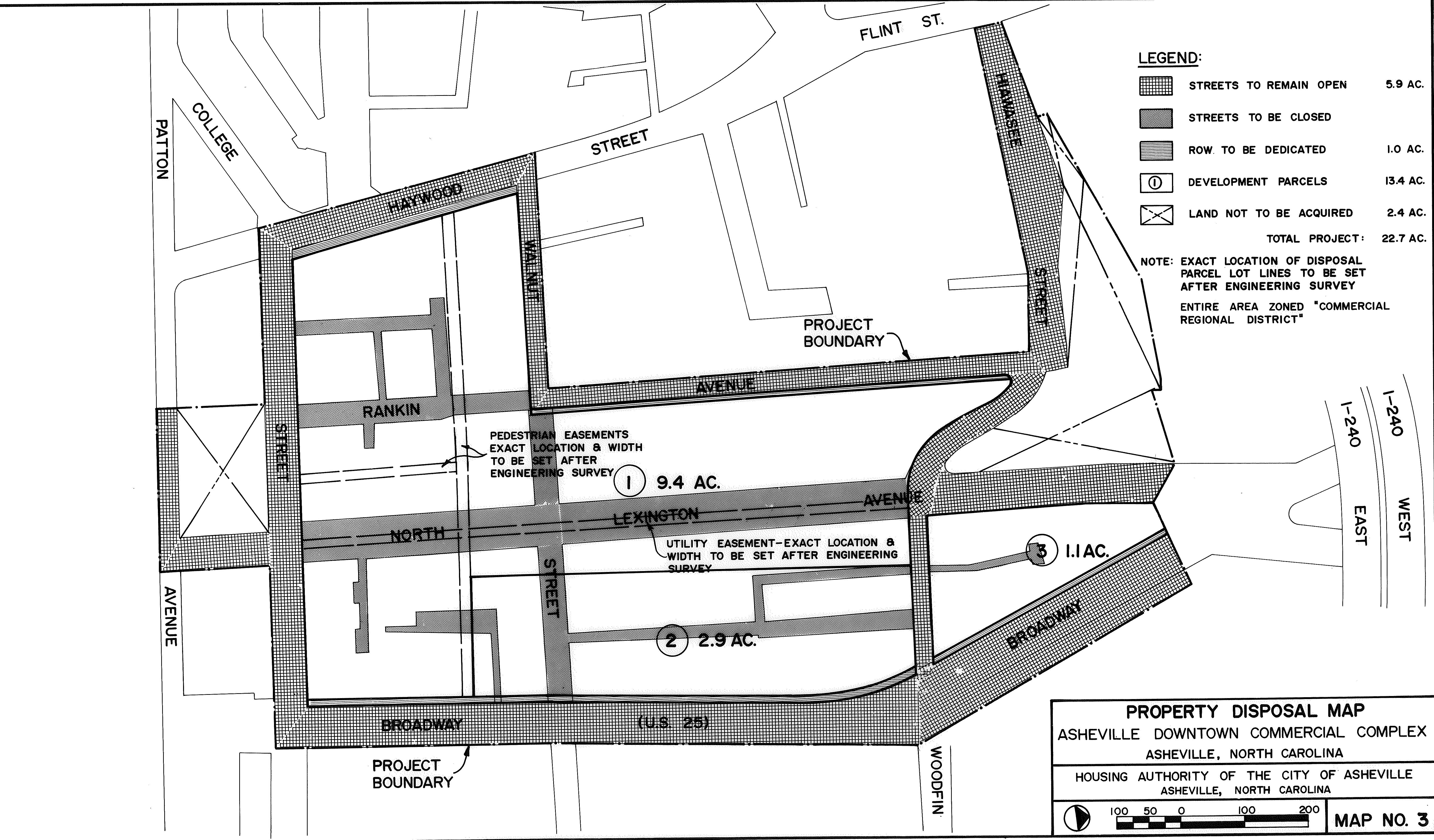

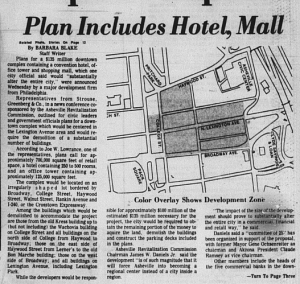

The text of the proposal notes that acknowledgement and certification of existing blight and certification of the downtown area as a non-residential redevelopment area was made by a resolution passed by the Planning and Zoning commission of the City of Asheville on November 10th, 1980. On August of 1981 The Housing Authority of the City of Asheville in cooperation with The City of Asheville, Division of Planning revised their final draft for the downtown redevelopment plan. This plan consisted of acquiring and tearing down 139 lots of land that covered approximately 22.7 acres of Downtown Asheville in order to build a new shopping mall. Many of these parcels were small, averaging less than 5,000 square feet. Commercial land occupied 54% of the project, 4% of the area was residential and transient housing and the remaining 42% were various public and semi-public streets.[ref]Housing Authority of the City of Asheville, and City of Asheville, Division of Planning. Asheville Commercial Complex Redevelopment Plan. PDF. 5.[/ref]

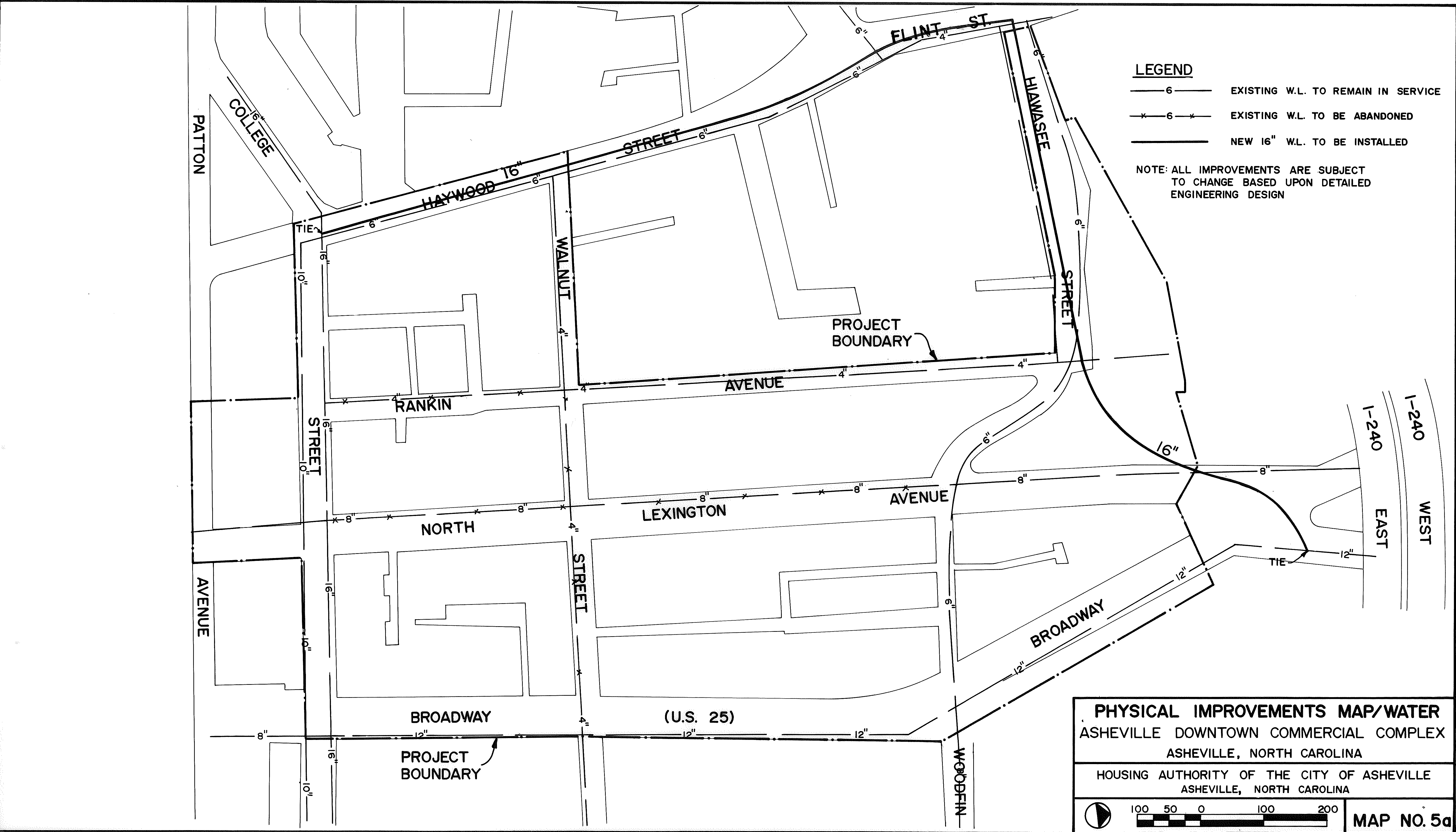

Occording to the proposal, once the land was acquired the project aimed to relocate any residents occupying the area of the would be commercial complex. The residents included 125 total businesses and 2 non-profit organizations adding up to a work force of 487. The ethnic make of these residents included 120 white non-minorities, 3 African Americans and 2 people of East Asian decent.[ref]Housing Authority of the City of Asheville, B-1[/ref] Beyond relocation, the proposed renewal effort included, demolition of the area and improvement to streets, side walks, water systems, sanitary sewer systems and storm water utilities. [ref]Housing Authority of the City of Asheville, 12-18[/ref]

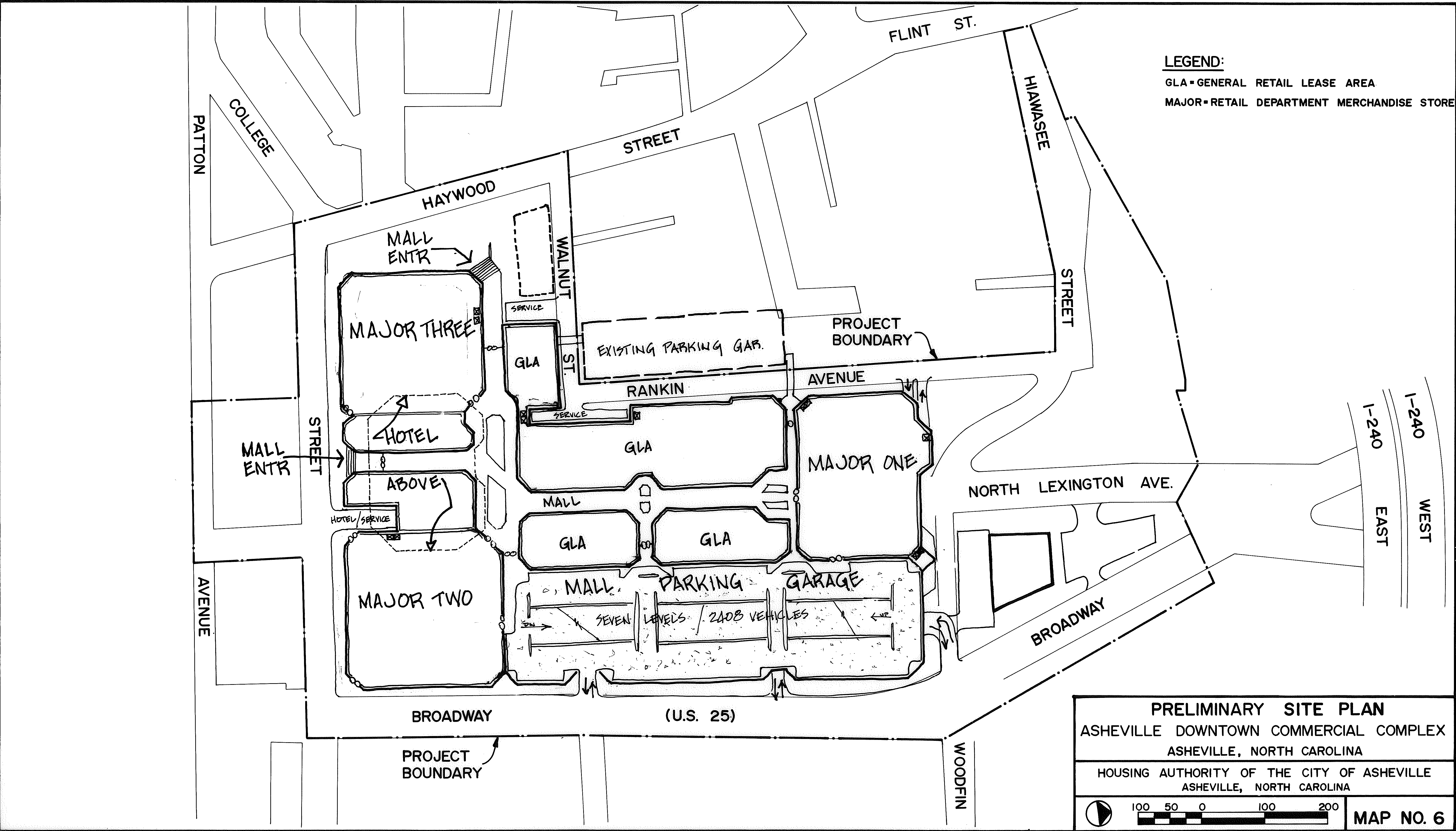

Land acquisition and improvements proposed in the redevelopment plan.

Most of the land proposed in the redevelopment plan would be for commercial development that was aimed to support the adjacent areas of the central business district and stimulate vitalization of the downtown area. The commercial development was set to build three major department stores containing a total of approximately 330,000 square feet, mall shops containing approximately 250,000 square feet, a fast food center containing approximately 13,000 square feet and a 300 room hotel.[ref]Housing Authority of the City of Asheville, 6[/ref]